Engineers love blueprints. We love diagrams, design docs, epics broken down into tickets, and plans for how every component will interact before the first line of code is written. Planning gives us the illusion of certainty - and sometimes, actual certainty. We’ve been trained to architect solutions like we’re building suspension bridges: carefully, deliberately, with no room for surprises. But here’s the quiet truth: not every problem deserves that level of foresight. Sometimes the best solution doesn’t start with a blueprint - it starts with a seed.

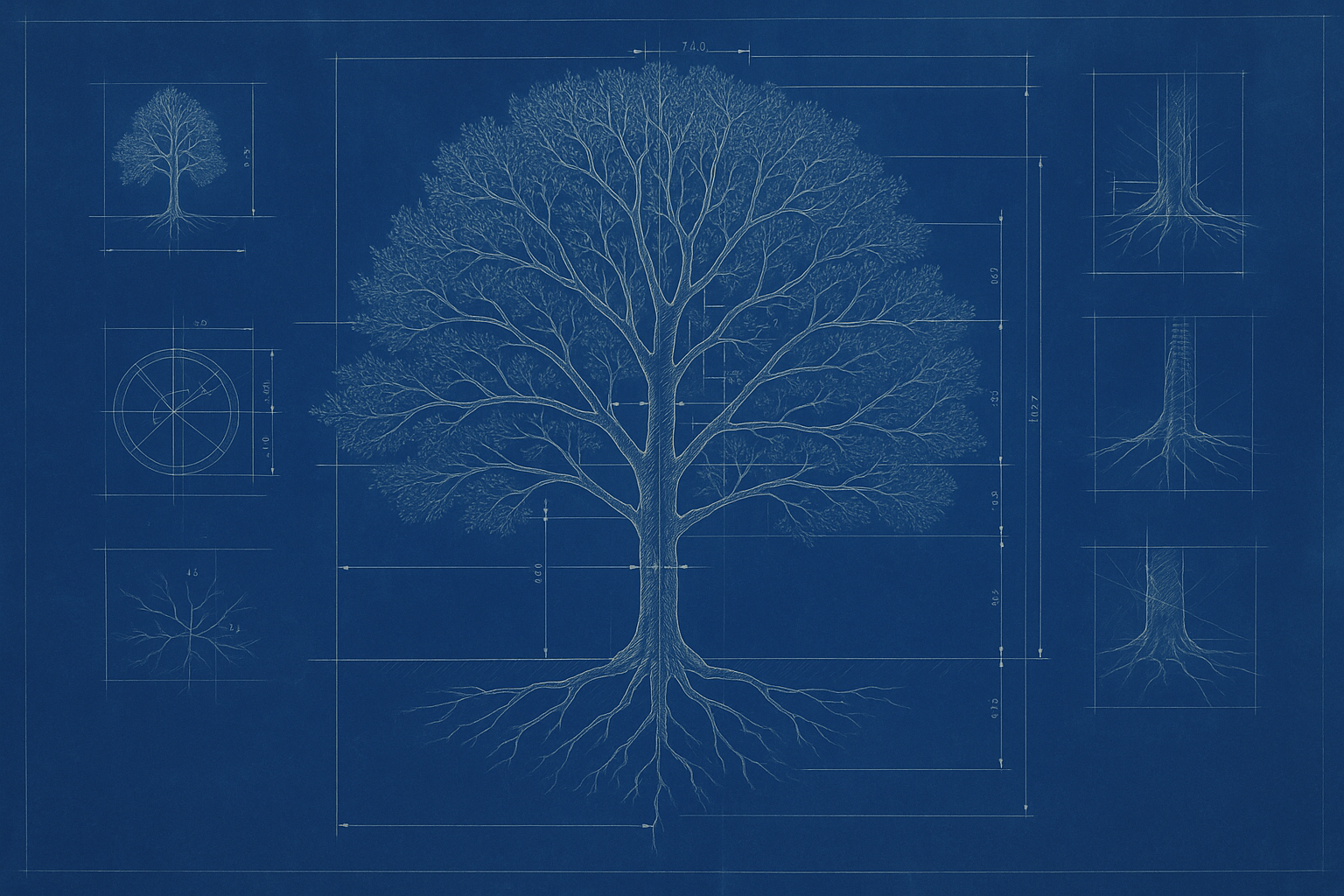

A technical drawing for an unplannable process.

Author George R.R. Martin, of Game of Thrones fame, once described two types of writers: architects and gardeners. Architects plan everything ahead of time. They know the shape of the final product before they begin. Gardeners, on the other hand, plant a seed and see what grows. They don’t always know what the final structure will look like until they’ve lived with it for a while.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about how often this same split applies to engineering. There are times when it makes sense to fully design the system up front - when the constraints are clear, the interfaces well understood, and the cost of a mistake is high. In those moments, channeling your inner architect is not just good practice, it’s critical.

But there’s a whole category of engineering work where that approach breaks down. Sometimes, you don’t yet understand the problem space. Sometimes you don’t have enough user input, or the requirements are more suggestion than specification. Or maybe the system you’re working on is so old - and so duct-taped together - that trying to plan it all out in advance is like drawing blueprints for a haunted house. In those cases, gardening might be the only strategy that works.

When you garden a solution, you start small. You build just enough to learn something. You let early insights shape the next step. It’s not that you’re avoiding planning; it’s that the act of building is part of the planning. You’re uncovering constraints that no one thought to mention. You’re discovering edge cases not because you theorized them, but because you tripped over them in practice. You’re growing something useful through iteration, not prescription.

This approach often feels uncomfortable, especially in engineering cultures that worship at the altar of the proper plan. But too much planning can backfire. We’ve all seen projects that died under the weight of their own architecture - beautiful diagrams that never shipped, or platforms so generic and extensible that nobody actually wanted to use them. That’s the risk of forcing an architect’s approach where a gardener’s mindset would’ve done better. You end up building a temple for a religion no one follows.

To be clear, gardening isn’t the absence of discipline. It’s not hacking. It’s a deliberate strategy for tackling ambiguous or fast-changing work. Prototyping is gardening. Spiking to explore an idea is gardening. Starting with the simplest thing that could possibly work and seeing how far it can take you? Definitely gardening.

For Data Engineers, this often shows up in the shape of small, fast iterations. Prototyping a new streaming use case with limited access to real-time data? That’s a gardener move. Trying to wrangle a third-party data source with undocumented edge cases and missing fields? You’ll probably discover more by digging in than by diagramming your way around it.

On the flip side, some work absolutely demands an architect’s mindset. Designing a data pipeline that feeds financial reports? That’s an architect job. Rolling out schema changes across multiple ingestion sources? Please, for everyone’s sanity, plan it.

The key is knowing when each mode is appropriate. There are projects that need structure, predictability, and careful integration from day one. But there are just as many that benefit from starting rough, learning fast, and refactoring your way to clarity. Some of the best solutions I’ve seen didn’t arrive fully formed - they evolved through exploration. They weren’t planned into existence; they were grown.

In practice, most meaningful engineering work falls somewhere between the two extremes. We plan enough to avoid chaos, but we leave space for discovery. Maybe you sketch a loose outline of where you think the system should go, but stay ready to redraw it. Maybe you design the scaffolding, but don’t fill in all the rooms until you’ve walked through them. The trick is not to pick a side permanently, but to know which hat to wear for the problem in front of you.

So next time you’re staring at a vague ticket, or someone asks you to “just figure out” how to connect some ancient pipeline to a bleeding-edge solution, ask yourself: Is this really something I can plan end-to-end? Or should I plant something small, water it, and see where it grows?

Sometimes the best architecture starts with a bit of gardening.